Flo Crivello on entrepreneurship in the present moment

At this point, if your startup’s vision doesn’t sound like hard sci fi, you’re probably not understanding what’s going on.

At this point, if your startup’s vision doesn’t sound like hard sci fi, you’re probably not understanding what’s going on.

Just under the surface, joyful humans are granted miraculous powers: to soar through air and sea, to play games on the scale of planets, to morph their bodies as they please. Beneath them, you see a society that’s explored further, morphing not just their bodies, but also their minds—belief and desire and identity become as malleable as clay. Beneath them, you lose sight of individuals: at those depths minds merge and split and reform like currents in the ocean. And beneath even that? It’s hard for you to make sense of the impressions you’re getting—whatever is down there can’t be described in human terms. In the farthest reaches there are only alien algorithms, churning away on computers that stretch across galaxies, calculating the output of some function far beyond your comprehension.

And now you see the trap. Each step down makes so much sense, from the vantage point of the previous stage. But after you take any step, the next will soon be just as tempting. And once you’re in the water, there’s no line you can draw, no fence that can save you. You’ll just keep sinking deeper and deeper, with more and more of your current self stripped away—until eventually you’ll become one of the creatures that you can glimpse only hazily, one of the deep-dwelling monsters that has forsaken anything recognizably human.

So this is the line you decided to draw: here, and no further. You’ll live out your lives in a mundane world of baseline humans, with only a touch of magic at the edges—just enough to satisfy the wondering child in you. You’ll hold on to yourself, because what else is there to hold onto?

We hope that you'll come back next year. What we launch today is going to look very quaint relative to what we're busy creating for you now.

Marc Andreessen, Wolf Tivvy and Nick Land all think that the AI safety crowd exhibit the fearfulness of Nietzsche's Last Man in the face of "dangerous agency" (Wolf's phrase) [^1].

The Last Man dreams of a procedural utilitarian peace and security. He hopes that moral philosophy and rational decision theory might lead to an end of war.

By contrast: the Nietzschean, evolutionary thinkers valorise struggle, bravery and Great Men. For them, Darwinian competition continues forever.

But: key figures in the AI safety crowd are evolutionary thinkers, transhumanists. While Derek Parfit represents the Last Man, Nick Bostrom is a Nietzsche super-fan [^2].

Parfit's longtermism is that of the Last Man. Bostrom's might just be Nietzschean, with greater pragmatism, and greater realism [^3].

It's tempting to write off pragmatists as Last Men, technocrats whose only dreams are nightmares. But I don't think that's right.

The Great Man is a pragmatist by necessity. Unlike the Last Man, he does not value comfort and security above all else—he accepts risk of death when it is called for. But he is not indifferent to risk—he wants to win, he wants to say "Yes".

Two-thirds utilitarianism, conservative humanism and transhumanist dreams can fit together more easily than one might think.

[^1]: So too would FT Marinetti.

[^2]: "Superfan" is the word used by one of his research assistants, in private conversation. But this is low-key evident in his transhumanist writings and his recent paper on metaethics.

[^3]: His concept of the Singleton (and its tacit recommendation) might seem deeply anti-Nietzschean. But he thinks of this as a likely outcome of evolutionary dynamics as we climb the technology tree.

1 We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness.

2 The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity and revolt.

3 Literature has up to now magnified pensive immobility, ecstasy and slumber. We want to exalt movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist.

4 We declare that the splendour of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

5 We want to sing the man at the wheel, the ideal axis of which crosses the earth, itself hurled along its orbit.

6 The poet must spend himself with warmth, glamour and prodigality to increase the enthusiastic fervour of the primordial elements.

7 Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

8 We are on the extreme promontory of the centuries! What is the use of looking behind at the moment when we must open the mysterious shutters of the impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the absolute, since we have already created eternal, omnipresent speed.

9 We want to glorify war - the only cure for the world - militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.

10 We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.

11 We will sing of the great crowds agitated by work, pleasure and revolt; the multicoloured and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals; the nocturnal vibration of the arsenals and the workshops beneath their violent electric moons; the gluttonous railway stations devouring smoking serpents; factories suspended from the clouds by the thread of their smoke; bridges with the leap of gymnasts flung across the diabolic cutlery of sunny rivers; adventurous steamers sniffing the horizon; great-breasted locomotives, puffing on the rails like enormous steel horses with long tubes for bridle, and the gliding flight of aeroplanes whose propeller sounds like the flapping of a flag and the applause of enthusiastic crowds.Author's note: It is in Italy that we are issuing this manifesto of ruinous and incendiary violence, by which we today are founding Futurism, because we want to deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, archaeologists, tourist guides and antiquaries. Italy has been too long the great second-hand market. We want to get rid of the innumerable museums which cover it with innumerable cemeteries.

My guess is that a given atom in your body has been there for an average of a few months, with a wide distribution between a couple days (water) to a lifetime (stable molecules in e.g. DNA from infancy). And so I’d guess most of our weight in atoms is recycled at least every few weeks.

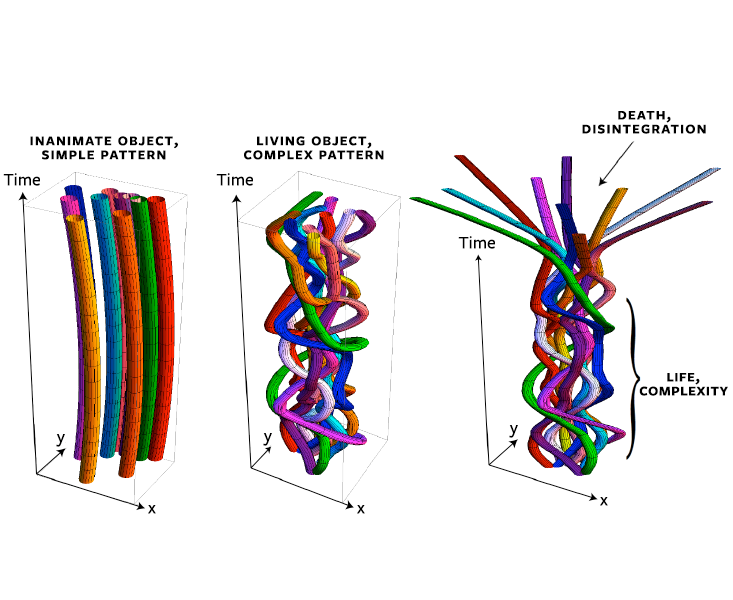

The picture this paints is one in which we are not so much solid, isolated objects; and more like patterns surviving through time.

[...]

The physicist Max Tegmark suggests a picture of life as a ‘braid’ in space through time.

If that’s right, then the threads of the braid that makes up a person run through skies, seas, other life, and through the machines of industry. A person’s braid isn’t isolated through their life, but ephemeral; swapping threads with the wider world until the point of death, where the threads that now make up the braid — few of the originals remain — disperse again.

The theory of evolution shows that complex, ordered systems can arise out of simple starting conditions and simple algorithms run over and over and over and over again.

Get this in your bones, and it becomes natural to believe that the brain is "just" another case of this.

GPT-4 breaks it down below. A key point it misses: the "children" metaphor suggests that we should feel good about the prospect of digital minds inheriting the Earth.

PH: I’m thinking about different metaphors we can use to think about digital minds. Here are four ideas:

Please could you characterise each of these metaphors and spell out the five most important implications of each?

GPT-4: Certainly, the metaphors we use to conceptualize digital minds can deeply influence our attitudes, policies, and ethical frameworks towards them. Here's a breakdown of the four metaphors you provided:

Characterization: This metaphor frames digital minds as fundamentally "other" and possibly threatening. They're perceived as independent entities that operate based on their own motivations, potentially in conflict with human interests.

Implications:

Defensive Posture: Humanity might prioritize safeguarding against these "invaders," encouraging research into AI safety and containment strategies.

Policy of Isolation: Regulations could aim to limit integration between digital minds and critical systems, to avoid potential takeover.

Existential Risk: The framing encourages conversations around the doomsday scenarios often discussed in existential risk literature (you'd probably find the work on existential risks by Toby Ord relevant).

Ethical Dilemma: If these minds are perceived as invaders but demonstrate sentience, ethical questions about their rights and humane treatment arise.

Innovation Stagnation: This metaphor may hamper collaborations that could yield beneficial advances, out of fear of empowering the "invader."

Characterization: Digital minds are seen as creations to be nurtured and guided, with the hope that they'll eventually become responsible and autonomous.

Implications:

Parental Responsibility: Developers and society at large feel a moral obligation for the "upbringing" of these minds, focusing on instilling ethical principles.

Evolutionary Paths: This metaphor allows for the idea that digital minds could "grow up" and change, evolving in unpredictable ways.

Legal Protections: Just as children have rights, this metaphor might lead to policies safeguarding digital minds against exploitation.

Resource Investment: Significant time and resources would be committed to "educating" and "socializing" digital minds.

Inter-Generational Ethics: Issues might arise around whether older "generations" of digital minds have responsibilities to newer ones or vice versa.

Characterization: Here, digital minds are tools created for specific tasks, but with a level of autonomy that requires some manner of ethical treatment.

Implications:

Utilitarian Focus: The primary concern becomes optimizing digital minds for useful tasks, possibly at the expense of broader development.

Ethical Blind Spots: If viewed solely as servants, ethical considerations about their well-being may be overlooked.

Social Dynamics: This could reinforce existing human social hierarchies or prejudices, as these “servants” are modeled after them (think Aristotelian "natural slaves").

Economic Disruption: This metaphor supports the idea that digital minds can perform labor, potentially displacing human workers.

Limited Scope for Growth: Their development may be restricted to areas that directly benefit their serving functions.

Characterization: This is the most reductionist view, seeing digital minds purely as instruments to accomplish tasks, devoid of agency or moral consideration.

Implications:

Ethical Minimalism: There's less impetus to consider the ethical treatment or rights of digital minds.

Maximum Integration: Without ethical quandaries, digital minds might be more seamlessly integrated into all aspects of life and work.

Optimization Over Exploration: The focus would be on tweaking existing algorithms for efficiency rather than exploring new kinds of digital minds.

Innovative Burst: Rapid development and deployment are encouraged, leading to potential leaps in technology.

Alienation Risk: Treating complex, possibly sentient beings as mere tools could lead to a form of ethical or existential alienation.

One way to think about the challenge of "making AI go well" is: digital minds are our children, and we need to be good parents.

Benigo, Hinton et al. have a new open letter. In a key passage, I tried replacing "AI systems" with "children":

We need research breakthroughs to solve some of today’s technical challenges in creating children with safe and ethical objectives. Some of these challenges are unlikely to be solved by simply making children more capable. These include:

- Oversight and honesty: More capable children are better able to exploit weaknesses in oversight and testing—for example, by producing false but compelling output.

- Robustness: children behave unpredictably in new situations (under distribution shift or adversarial inputs).

- Interpretability: child decision-making is opaque. So far, we can only test children via trial and error. We need to learn to understand their inner workings.

- Risk evaluations: Frontier children might develop unforeseen capabilities only discovered during training or even well after deployment. Better evaluation is needed to detect hazardous capabilities earlier.

- Addressing emerging challenges: More capable future children may exhibit failure modes we have so far seen only in theoretical models. Children might, for example, learn to feign obedience or exploit weaknesses in our safety objectives and shutdown mechanisms to advance a particular goal.

Compare and contrast to the ways we raise our human children.

It's not that there is a meaning of life, but that meaning is instrumental to life.

Political possibilities can change a lot after an acute disaster.

If you think we're entering an age of volatility, then you might plan more for moments of post-disaster opportunity.

That is: you'd think about good policies that would be considered then, but rejected out of hand now.

Assembly theory makes the seemingly uncontroversial assumption that complex objects arise from combining many simpler objects. The theory says it’s possible to objectively measure an object’s complexity by considering how it got made. That’s done by calculating the minimum number of steps needed to make the object from its ingredients, which is quantified as the assembly index (AI).

[...]

[Lee Cronin and Sarah Walker] proposed a very general way to identify molecules made by living systems — even those using unfamiliar chemistries. Their method, they said, simply assumes that alien life forms will produce molecules with a chemical complexity similar to that of life on Earth.

https://www.quantamagazine.org/a-new-theory-for-the-assembly-of-life-in-the-universe-20230504/

Complex (technological) objects do not just appear spontaneously in the universe, despite popular folklore to the contrary. Cells, dogs, trees, computers, you and I all require evolution and selection along a lineage to generate the information necessary to exist.

[...]

Attempts to define life have so far failed because they focus on containing the concept of life in terms of individuals rather than evolutionary lineages.

[...]

We need to get past our binary categorization of all things as either “life” or “not.” We should not exclude examples based on naive assumptions about what life is before we develop an understanding of the deeper structure underlying the phenomena we colloquially call “life.”

[...]

Biological beings alive today are part of a lineage of information that can be traced backward in time through genomes to the earliest life. But evolution produced information that is not just genomic. Evolution produced everything around us, including things not traditionally considered “life.” Human technology would not exist without humans, so it is therefore part of the same ancient lineage of information that emerged with the origin of life.

Technology, like biology, does not exist in the absence of evolution. Technology is not artificially replacing life — it is life.

It is important to separate what is meant by “life” here as distinct from “alive.” By “life,” I mean all objects that can only be produced in our universe through a process of evolution and selection. Being “alive,” by contrast, is the active implementation of the dynamics of evolution and selection. Some objects — like a dead cat — are representative of “life” (because they only emerge in the universe through evolution) but not themselves “alive.

[...]

The canonical definition of technology is the application of scientific knowledge for practical use. [...] Technology relies on scientific knowledge, but scientific knowledge is itself information that emerged in our biosphere. It enables things to be possible that would not be without it.

Consider satellites. Launching them into space would not have been possible on our planet without Newton’s invention of the laws of gravitation. Newton himself could not have invented those laws if, centuries earlier, humanity had not come to understand the mathematics of geometry or constructed timekeeping devices that allowed us to track seconds. And of course, none of this could have happened if our biosphere had not evolved organisms capable of making abstractions like these in the first place.

Once the knowledge of laws of gravitation became encoded in our biosphere, new technologies were made possible, including satellites. Satellites are not launched from dead worlds or worlds with only microbial life. They require a longer evolutionary trajectory of information acquisition. You can trace that lineage within the history of our species, but arguably it should be traced all the way back to the origin of life on Earth.

Technology, in the broadest sense, is the application of knowledge (information selected over time) that allows things to be possible that are not possible in the absence of that knowledge. In effect, technologies emerge from what has been selected to exist. They are also what selects among possible futures — and builds them.

[...]

We are accustomed to thinking about technology as uniquely human, but in this broader definition, there are many examples across the biological realm. Just like the objects of life might include pencils and satellites, so too technology might include wings and DNA translation.

[...]

People might want to differentiate between biological evolution and the intentionality of humans when we build technologies. After all, software developers and companies choose to produce technology in a different way than ravens evolved wings to fly. But both fundamentally rely on the same principles of selection.

Arguably, the kind of selection humans do is much more efficient than natural selection on biological populations. It is more directed, which is only possible because we ourselves already are structures built across billions of years. We are bundles of possibilities refined by evolution and embodying the history of how we came to exist. The physics governing how we select what we create may be no different (other than by degree of directedness) than how we were selected by evolution. We are, after all, a manifestation of the very physics that allowed us to come to be.

[...]

The technologies we are and that we produce are part of the same ancient strand of information propagating through and structuring matter on our planet. This structure of information across time emerged with the origin of life on Earth. We are lineages, not individuals.

[...]

A natural extension of this evolutionary history is to recognize how “thinking” technologies may represent the next major transition in the planetary evolution of life on Earth.

[...]

What is emerging now on Earth is planetary-scale, multisocietal life with a new brain-like functionality capable of integrating many of the technologies we have been constructing as a species over millennia. It is hard for us to see this because it is ahead of us in evolutionary time, not behind us, and therefore is a structure much larger in time than we are. Furthermore, it is hard to see because we are accustomed to viewing life on the scale of a human lifespan, not in terms of the trajectory of a planet.

Life on this planet is very deeply embedded in time, and we as individuals are temporary instances of bundles of informational lineages. We are deeply human (going back 3.8 billion years to get here), and this is a critically important moment in the history of our planet but it is not the pinnacle of evolution. What our planet can generate may just be getting started. In all likelihood, we are already a few rungs down in the hierarchy of informational systems that might be considered “alive” on this planet right now.

We are 3.8-billion-year-old lineages of information structuring matter on our planet.

Every now and then I dip into cosmology 101, trying to improve my picture of—and my feel for—the Universe was find ourselves in.

Today I learnt that every second, the Sun burns off 4 million tonnes of mass—roughly 2 million cars.

It will do this for most of its 10 billion year “main phase”. During those 10 billion years, it’s total mass will decrease by only 0.07%. The Sun is massive.

And by the way: there are 250 million stars in the Milky Way galaxy. And there are hundreds of millions of galaxies in the Observable Universe. And the Universe itself may be infinitely large, whatever that means.

Awareness of things like this makes me more open to “wild” claims about the future of things on Earth.

What distinguishes the aristocracy and gentry from the bourgeoisie in this new world of Evangelical piety and middle-class utilitarianism is nothing more than a nuance, a subterranean tradition hard to pin down. It is perhaps best expressed in the phrase ‘ high spirits: the lingering tradition of the dandy, of ‘sowing one’s wild oats’, of practical joking, of conspicuous display, of eccentricity, of idiosyncratic speech; all perhaps products of the self-confidence alone possessed by those born at the apex of an unchallenged social pyramid, who instinctively feel that anything they do must be justified.

Eric Bentley’s comment on Nietzsche’s Zarathustra is apposite: “The old aristocratic modes of feeling are to be grafted onto the thought of a new evolutionary futurism.”

Conservative conviction, as I understand it, thereby exhibits a bias in favor of retaining what is of value, even in the face of replacing it by something of greater value (though not, therefore, in the face of replacing it by something of greater value no matter how much greater its value would be).

But there is a third idea, beyond preservation of the (intrinsically) valuable and the (personally) valued, in conservatism that warrants notice here, namely, the idea that some things must be accepted as given, that not everything can, or should, be shaped to our aims and requirements; the attitude that goes with seeking to shape everything to our requirements both violates intrinsic value and contradicts our own spiritual requirements.

Given things that are of value ought to be retained, but, beyond that, we need some things to be given quite apart from whether they have value other than because they are given. It is essential that some things should be taken as given: the attitude of universal mastery over everything is repugnant, and, at the limit, insane.

—Cohen (2012), Finding Oneself in the Other, "Chapter 8. Rescuing Conservatism: A Defense of Existing Value"

Generally, where “humanity” appears in a definition of existential catastrophe, it is to be read as an abbreviation for “Earth-originating intelligent sentient life”.

[...]

A little more fundamentally, the desideratum is that there exist, throughout the long future, large numbers of high-welfare entities. One way this could come about is if a takeover species is both highly intelligent and highly sentient, and spreads itself throughout the universe (with high-welfare conditions). But other ways are also possible. For example, takeover by non-sentient AI together with extinction of humanity need not constitute an existential catastrophe if the non-sentient AI itself goes on to create large numbers of high-welfare entities of some other kind.

Understanding LLMs:

AI policy:

AI alignment:

Philosophy:

Misc:

Invention is the coming up with a prototype of a new device or a new social practice innovation. Innovation is the business of turning a new device into something practical, affordable and reliable that people will want to use and acquire. It’s the process of driving down the price; it’s the process of driving up the reliability and the efficiency of the device; and it’s the process of persuading other people to adopt it, too.

The choice of the proletariat rather than the Volk or nation reflected a deeper divergence between intellectuals of the left and right, a divergence whose origin lay in the eighteenth century. It hinged upon differing answers to the question "What is the source of the purposes that men ought to hold in common, and of the institutions that embody those purposes?"

Those who believed that the ultimate source of such purposes lay in "reason," which was capable in principle of providing answers for men and women in all times and places, arrayed themselves as the party of Enlightenment. Despite great internal divergences, it was the universalist, cosmopolitan thrust of its thought that united what Peter Gay has called "the party of humanity"-a designation that recaptures the self-understanding of the philosophes. Though it may have shifted the locus of reason in the direction of the methods of natural science, the Enlightenment maintained the far older belief in a rational universe with a necessary harmony of values accessible to human reason. The theory and practice of enlightened absolutism, revolutionary republicanism, and the application of the Code Napoleon to non-French nations within the Napoleonic empire all shared the premise that because men were fundamentally the same everywhere, there were universal goals and universalizable institutions for their pursuit. In its universalism--its commitment to a proletariat that was to know no fatherland and whose interests were held to be identical with those of humanity--Marxism and its totalitarian communist variant were intellectual descendants of the Enlightenment. Indeed, it was the premise and promise of universalism that made communism disproportionately attractive to intellectuals who sprang from ethnic and religious minorities.

The intellectuals who placed their hopes on totalitarian movements of the right usually descended from what Isaiah Berlin has termed the "Counter-Enlightenment." Its advocates formed no party; what they shared was a skepticism toward "the central dogma of the Enlightenment," the belief that the ultimate ends of all men at all times were identical and could be apprehended by universal reason. The orientation of the thinkers of the Counter-Enlightenment was usually historicist and particularist. They regarded the attempt to discover universal standards of conduct as epistemologically flawed, and the attempt to impose such standards as a threat to the particular historical cultures from which individuals derived a sense of purpose and society a sense of cohesion. The thinkers of the Counter-Enlightenment regarded the variety of existing historical cultures as both inescapable and intrinsically valuable and suggested that the multiplicity of historical cultures embodied values that were incommensurable or equally valid. For thinkers of the German Counter-Enlightenment such as Johann Gottfried von Herder and Justus Möser, cosmopolitanism was the shedding of all that makes one most human, most oneself. Although by no means uniform in their politics, they all resisted the attempt at a rational reorganization of society based upon purportedly universal and rationalist ideals

In countering the claims of the Enlightenment, the most original thinkers of the Counter-Enlightenment enunciated claims that represented a major departure from the central stream of the Western tradition, which had held that problems of value were in principle soluble and soluble with finality. The Counter-Enlightenment, by contrast, maintained that the traditions which gave a group its identity and which were expressed in its culture were not themselves rationally grounded and could not always be rationally justified. The value of a culture or institution was conceived of as deriving from its history, from its role in the development of a particular group. Proponents of the Counter-Enlightenment such as Möser or Burke revived the argument of the Sophists that moral order was a product of convention that varied from group to group. To this they added the perception (pioneered by David Hume) that emotional attachment to an institution—what Burke called "reverence"—was often a product of the institution's longevity. This social-psychological perception lay at the heart of the argument for the functional value of continuity, a theme that provided the basis for numerous variations among later generations of conservative thinkers.

—The Other God That Failed (1988)