How well will it generalise?

We now know that “LLMs + simple RL” is working really well.

So, we’re well on track for superhuman performance in domains where we have many examples of good reasoning and good outcomes to train on.

We have or can get such datasets for surprisingly many domains. We may also lack them in surprisingly many. How well can our models generalise to “fill in the gaps”?

It’s an empirical question, not yet settled. But Dario and Sam clearly think “very well”.

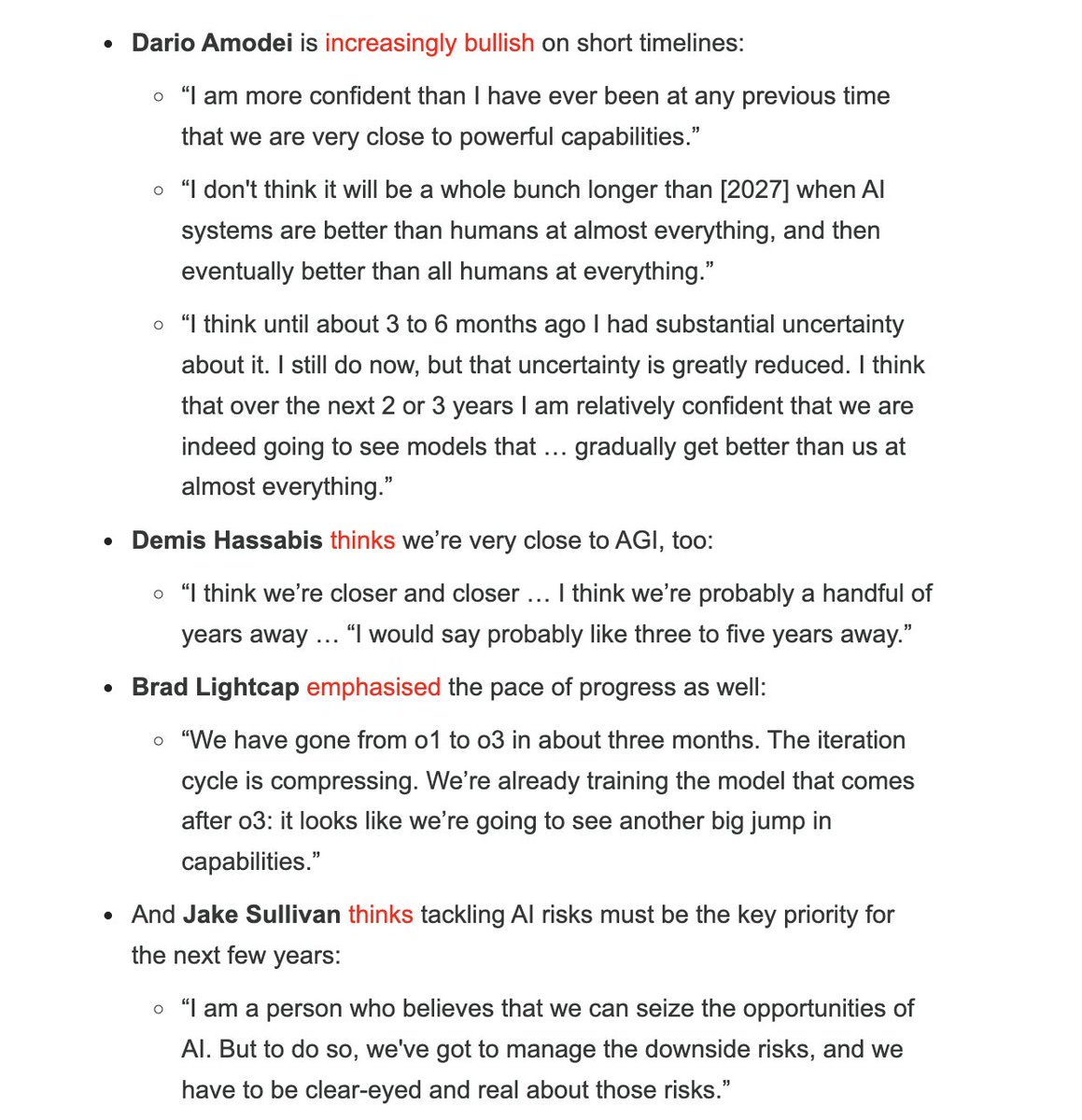

Dario, in particular, is saying:

I don’t think it will be a whole bunch longer than [2027] when AI systems are better than humans at almost everything, and then eventually better than all humans at everything.

And:

“I am more confident than I have ever been at any previous time that we are very close to powerful capabilities. […] I think until about 3 to 6 months ago I had substantial uncertainty about it. I still do now, but that uncertainty is greatly reduced. I think that over the next 2 or 3 years I am relatively confident that we are indeed going to see models that … gradually get better than us at almost everything.

Gwern doubts Dario’s view, but he’s not inside the labs, so he can’t see what they see.

Noam Brown on feeling the AGI

It can be hard to “feel the AGI” until you see an AI surpass top humans in a domain you care deeply about. Competitive coders will feel it within a couple years. Paul is early but I think writers will feel it too. Everyone will have their Lee Sedol moment at a different time. https://t.co/Sfi1IZOGSd

— Noam Brown (@polynoamial) January 19, 2025

Correct, except that competitive coders will be feeling it this year, if they aren’t already.

Ellsberg to Kissenger, on security clearance

“Henry, there’s something I would like to tell you, for what it’s worth, something I wish I had been told years ago. You’ve been a consultant for a long time, and you’ve dealt a great deal with top secret information. But you’re about to receive a whole slew of special clearances, maybe fifteen or twenty of them, that are higher than top secret.

“I’ve had a number of these myself, and I’ve known other people who have just acquired them, and I have a pretty good sense of what the effects of receiving these clearances are on a person who didn’t previously know they even existed. And the effects of reading the information that they will make available to you.

“First, you’ll be exhilarated by some of this new information, and by having it all — so much! incredible! — suddenly available to you. But second, almost as fast, you will feel like a fool for having studied, written, talked about these subjects, criticized and analyzed decisions made by presidents for years without having known of the existence of all this information, which presidents and others had and you didn’t, and which must have influenced their decisions in ways you couldn’t even guess. In particular, you’ll feel foolish for having literally rubbed shoulders for over a decade with some officials and consultants who did have access to all this information you didn’t know about and didn’t know they had, and you’ll be stunned that they kept that secret from you so well.

“You will feel like a fool, and that will last for about two weeks. Then, after you’ve started reading all this daily intelligence input and become used to using what amounts to whole libraries of hidden information, which is much more closely held than mere top secret data, you will forget there ever was a time when you didn’t have it, and you’ll be aware only of the fact that you have it now and most others don’t….and that all those other people are fools.

“Over a longer period of time — not too long, but a matter of two or three years — you’ll eventually become aware of the limitations of this information. There is a great deal that it doesn’t tell you, it’s often inaccurate, and it can lead you astray just as much as the New York Times can. But that takes a while to learn.

“In the meantime it will have become very hard for you to learn from anybody who doesn’t have these clearances. Because you’ll be thinking as you listen to them: ‘What would this man be telling me if he knew what I know? Would he be giving me the same advice, or would it totally change his predictions and recommendations?’ And that mental exercise is so torturous that after a while you give it up and just stop listening. I’ve seen this with my superiors, my colleagues….and with myself.

“You will deal with a person who doesn’t have those clearances only from the point of view of what you want him to believe and what impression you want him to go away with, since you’ll have to lie carefully to him about what you know. In effect, you will have to manipulate him. You’ll give up trying to assess what he has to say. The danger is, you’ll become something like a moron. You’ll become incapable of learning from most people in the world, no matter how much experience they may have in their particular areas that may be much greater than yours.”

….Kissinger hadn’t interrupted this long warning. As I’ve said, he could be a good listener, and he listened soberly. He seemed to understand that it was heartfelt, and he didn’t take it as patronizing, as I’d feared. But I knew it was too soon for him to appreciate fully what I was saying. He didn’t have the clearances yet.

Airbus: upgrading their software UI from “crappy” to “best practice” helped 4x the pace of A350 manufacturing

These are all sort of basic software things, but you’ve seen how crappy enterprise software can be just deploying these ‘best practice’ UIs to the real world is insanely powerful. This ended up helping to drive the A350 manufacturing surge and successfully 4x’ing the pace of manufacturing while keeping Airbus’s high standards of quality.

Michael Nielsen and others on privacy

Why does privacy matter? What are the best principled arguments for it? Where to set the boundary [i.e., when is it best to require that certain actions be more broadly known]?

— Michael Nielsen (@michael_nielsen) October 3, 2024

My own answer to this bundle of questions isn't very good. I've read a few classic books, papers,…

It's tempting to give purely consequence-based arguments (in terms of forestalled knowledge and invention and life experience and so on). But while I agree, somehow that kind of argument seems too small. Some sort of right to privacy seems to create a fundamentally different…

— Michael Nielsen (@michael_nielsen) October 3, 2024

My favorite defense of privacy rights is that in order to have other rights such as freedom of opinion, you need a private domain where you can explore your options without being judged by others.

— Anders Sandberg (@anderssandberg) October 3, 2024

(related to surveillance and power) the freedom to explore a diversity of behaviors increases the total resilience of a system. If the option exists to centrally surveil/control behavior, you get more homogenization / monocrop effect and more potential for catastrophic failure.

— Gordon (@gordonbrander) October 3, 2024

An interesting framing: https://t.co/lEEjgw9vOt

— Michael Nielsen (@michael_nielsen) October 3, 2024

E. O. Wilson has pointed to human experience of shame and guilt as consequences of our evolutionary origins as a social species. It's interesting then to enshrine (limited) protection against that shame and guilt in…

Interesting to think of privacy as an extension of Madison's separation of powers. Madison was aimed at powerful institutions; privacy gives a kind of fundamental power and insulation of individuals against institutions

— Michael Nielsen (@michael_nielsen) October 3, 2024

Put another way: privacy encourages us individually to go to 11. And it's really valuable to have space for that: https://t.co/bJHf4j2xQ3

— Michael Nielsen (@michael_nielsen) October 3, 2024

Interesting to realize how many of these arguments would still be largely true if we only had a right to privacy 12 hours a day

(Connected…

Another argument: the right to privacy protects the power of individuals to act against corruption of the surveilling power. For that reason, we'd expect that degree of corruption to be [very roughly] inverse to the privacy of individuals. In that sense, a strong right to…

— Michael Nielsen (@michael_nielsen) October 3, 2024